The best new ideas often come from improving old ones.

Inspiration can come from refinement: the improvement of less creative thought.

TRAINING INSPIRATION (part five)

Wait. Do we even know exactly what an idea is? Let’s go back to that font of knowledge, the Oxford English Dictionary. The word denotes “an image in the mind.” It’s something that occurs to you, a picture that pops up.

The OED also says an idea is a conception, implying that your mind gives birth.

Here’s where the etymology gets really interesting (assuming you’re a fellow word nerd): the term idea originally appears in Plato’s dialogues. His ideia was an ideal form, the true essence of a thing, “an eternally existing pattern or prototype,” something pure and unique. That famous cave analogy—the one where the benighted cave prisoners could only see the shadows outside—was all about ideia.

In examining himself, Montaigne refined humanity.

Much of the time, the reality we witness represents only the shadows of the true nature of things. It takes a philosopher (or, in my case, the OED) to see the truth behind everything. Michel de Montaigne, a fan of Plato’s, decided to drill down to the ideia of humanity by studying a single person: himself.

He started with a Platonic syllogism:

Humans are fundamentally alike.

I am human. Therefore:

If I assay myself, I assay humankind.

Montaigne wrote short pieces about his life, his feelings, his relationship to his cat—wherever his mind strayed—all in the attempt to “assay” himself (essais in French). He was using a mineralogical metaphor: to assay a substance is to discover its purest original components. And so he invented the personal essay as an exploration of the very idea of humanity.

But humanity wasn’t Montaigne’s idea. It obviously existed already. His ingenious concept actually combined two ideas: humanity, and the process of assaying. He combined the two to create a brand new thought molecule, the essay.

In a four-decade career as an editor, I have found editing more rewarding than writing. For one thing, I’m better than editing. That may be one reason why my novel, The Prophet Joan, took more than 15 years to write. When it stopped being fun, I left it off. When I finally had the stuff of a novel, an actual manuscript, I realized that the plot was terrible. So I spent a year or so restructuring the thing. Once the plot seemed right, I rewrote every line, paragraph, page, and chapter. And rewrote again. And again. And…I can’t remember how many drafts the book went through. I just messed with it when I felt like it.

This may sound like torture, and it may be for you, but I prefer rewriting to writing. For many years, I’ve writers much more talented than I am, and made them even better. When I write, I do so in the confidence that I can edit whatever dreck I come up with. It still won’t be literature—the Muses passed me by long ago—but I can refine and distill down to essential ideas, with a clarity and rhythm that please at least me. The results have been undeniable; Thank You for Arguing, my one bestseller, went through seven drafts after my agent sold my proposal to the publisher. My son George has me beat; he went through 34 drafts of his college essay. It ended up being read to the incoming students at his college.

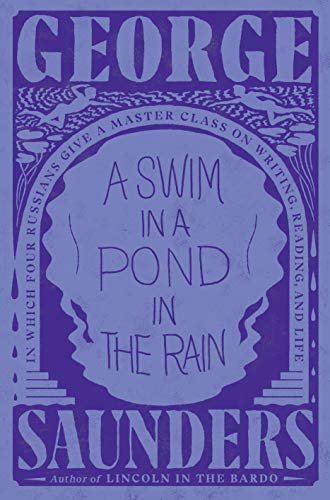

George Saunders says that revision is a matter of taste. Most of us are better readers than writers. When we read a sentence we’ve written, we should apply our reading chops to make it better. There’s no perfect result. In his book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain (every aspiring writer—and passionate reader for that matter—should buy it), Saunders offers a translation exercise using the Russian writer Isaac Babel. He lists five published translations of a single sentence in a Babel short story. Each sentence is great. Each sentence is significantly different.

In verdure-hidden walks wicker chairs gleamed whitely.

Wicker chairs, gleaming white, lined paths overhung with foliage.

And so on. Then Saunders goes on to write his own version, and then to rewrite his rewrite. Each version is great. Which one is the best? That’s the point: it’s a matter of taste, which comes from you.

Saunders’ appendices make ideal rewriting exercises.

EXERCISE: I strongly urge you to buy A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, and to do the exercises in the appendices. Saunders pitches them as writing exercises. But for the most part, they’re really re-writing exercises.

What does this have to do with inspiration? I think back to Acts 2, in which the fiery-tongued breath of God comes to the apostles, causing each one to mouth a different translation of prophecy. Each speaks a different language, individually.

Inspiration, I think, is an individual phenomenon. We can wait for it, prompt it, play with combinations of existing ideas, refine a half-formed idea into a Platonic ideia of your intentions. But the inspiration is yours alone.

In the next post, I’ll show how inspiration often comes from our own glorious screwups.